A Onetime White House and Wall Street Darling, Argentina Feels Jilted by Bolsonaro Buzz

On the night of the Brazilian election, Argentine President Mauricio Macri sent well wishes to the president-elect. “Congratulations to Jair Bolsonaro for your win in Brazil!” he tweeted. “I hope we will work together soon for the relationship between our countries and the wellbeing of Argentines and Brazilians.” Later, Mr. Macri called his future counterpart and invited him to visit Argentina.

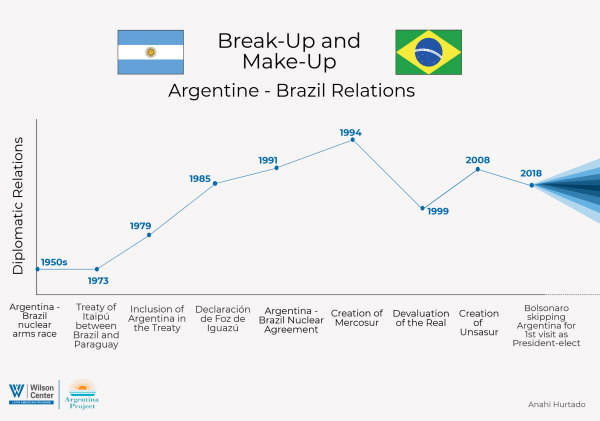

Despite that outreach, Mr. Bolsonaro broke with tradition and decided that his first foreign visit as president-elect would be to Chile, not Argentina. “Chile is the great Latin American model,” he explained. “It has a good education system, it develops technologies and it trades with the whole world.” Brazil’s future finance minister, Paulo Guedes, was even more blunt. “Argentina is not a priority,” he said.

Though Mr. Guedes later apologized, his insult heighted the sense of unease in Buenos Aires over the implications of Mr. Bolsonaro’s unexpected political rise.

Even before the Brazilian election, Argentina had faced an uncertain political and economic future heading into next year’s election. It is suffering its worst recession since 2001, and Mr. Macri’s decision to solicit International Monetary Fund assistance undermined his strategy to balance the budget gradually and at minimal political and social cost. Low growth, high inflation and spending cuts have cut into the president’s popularity and robbed him of his political capital. Though lawmakers recently approved his proposed budget for 2019, Mr. Macri’s legislative agenda has otherwise ground to a halt, including labor reform.

Now, enthusiasm for Mr. Bolsonaro’s promised reforms is making Argentine authorities even more anxious. The South American neighbors like to portray themselves as partners, they are also rivals, and not only on the soccer field. The two giants compete for geopolitical influence, export markets and foreign investment. For these reasons, some in Argentina feel pressured by Mr. Bolsonaro’s commitment to deepen the reforms of Brazil’s outgoing Temer administration.

Mr. Bolsonaro, a hard-right nationalist, has drawn scorn from international human rights organizations for his troubling comments about minority groups, and his nostalgia for Brazil’s dictatorship. But he has earned cautious optimism from investors; his October election led to a rally for the Brazilian currency and stock market. One reason for this enthusiasm is Mr. Guedes, the University of Chicago-trained economist who will serve as a Domingo Cavallo-style super minister, and who has been an outspoken proponent of deficit reduction; pension reform; and opening Brazil’s notoriously closed economy. Mr. Bolsonaro also plans to name apro-privatization economist to run Brazil’s state-owned oil company, Petrobras, and to demote Brazil’s once powerful labor ministry to a secretariat, likely under Mr. Guedes’s supervision. Investors hope the reforms, including tax cuts, will strengthen Brazil’s fragile recovery from its deep recession in 2014.

There are doubts about how much Mr. Bolsonaro can accomplish without a congressional majority. Moreover, if Mr. Bolsonaro manages to eliminate Brazil’s deficit in two years, Brazil likely will experience another recession, which could sap support for his administration. Still, for Argentina, the prospect of substantial economic reforms in Brazil, a far larger market, is nerve-racking. Should Brazil falter, it would reduce demand for Argentine goods in Argentina’s largest export market. Should Brazil succeed, it could divert foreign investment, and highlight Mr. Macri’s failure to reform Argentina’s protectionist and anti-competitive labor and industrial policies.

On trade, Mr. Bolsonaro’s skepticism about Mercosur – his team hascriticized the bloc as a “hindrance to free trade” – could bolster Mr. Macri’s efforts to promote free trade agreements between Mercosur and its partners, such as the European Union. But it could also lead Mr. Bolsonaro to abandon the bloc and implement unilateral reductions in tariffs that would deeply harm Argentine competitiveness in the Brazilian market. Argentina could stand to lose even more if Brazil revisits the Argentine-Brazilian auto pact, which was recently renegotiated. The economic relationship between Argentina and Brazil depends a great deal upon goodwill between the two countries’ presidents.

The new Brazilian government also threatens to diminish Argentina’s geopolitical clout. Mr. Bolsonaro’s admiration for Mr. Trump has clearly won over the National Security Council. John Bolton, Mr. Trump’s national security adviser, dedicated much of his November 2 Latin America speech to attacking the governments in Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela. But he paused to celebrate the election of Mr. Bolsonaro, whom he called a “likeminded” leader. Mr. Bolton also mentioned the U.S. partnership with Argentina, but his embrace of Brazil led one Argentine analyst, Francisco de Santibañes, from the Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales (CARI), to lament that, “Buenos Aires will not be able to receive the same kind of privileged treatment it has received so far.”

Mr. Bolsonaro’s election was hardly the first external development to threaten Mr. Macri’s reform agenda.

When Mr. Macri was elected in 2015, the liberal international order seemed secure, cradled by internationalists such as Barack Obama, Angela Merkel and Justin Trudeau. As Mr. Macri sought to reintegrate Argentina into the international community, both politically and economically, the world seemed to be moving in the same direction. For a time, the outside world rewarded Mr. Macri. Mr. Obama visited Buenos Aires in 2016, and investors followed closely behind, lending the billions of dollars necessary to permit a gradual reduction in public spending. (In all, Argentina’s government borrowed $161 billion in its first two years in office, including through a 100-year bond issued last year.)

But in time, the global environment turned hostile. Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 U.S. election to a trade skeptic, whose protectionist policies shut out Argentine biodiesel – its top export to the United States – from the U.S. market. Meanwhile, rising interest rates increased concerns about Argentina’s budget deficit and its pile of dollar-denominated debt, leading to capital flight earlier this year and a rapid peso devaluation.

So far, Mr. Macri’s government has survived this tumult, though not without a few bruises.

Significantly, he has preserved the close relationship with the United States that he established under Mr. Obama. That was not as simple as it seems. Beyond the policy disagreements with the Trump administration – ranging from commerce to climate – there was also bad blood. Most analysts assumed Mr. Macri and Mr. Trump, as businessmen turned politicians, would be simpatico. But in fact, the Macri and Trump families had once competed bitterly over a New York City real estate deal in the 1980s. Nevertheless. Mr. Macri and Mr. Trump appear to get along personally. Mr. Trump, for example, has been a vocal supporter of Argentina, backing the IMF bailout and Argentina’s membership in the OECD.

Now, as Argentina awaits the January 1 inauguration of another populist outsider, this time in Brazil, it remains to be seen how the Argentine government will manage its latest international surprise.

For more analysis on the potential impacts of Jair Bolsonaro’s election for Latin America, read our piece in World Politics Review, “If Brazil Elects Bolsonaro, Venezuela’s Migration Crisis Will Get Even Worse.”

Tweet: Tweet

Invite a friend to your weekly asado, and tell a friend about ours.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment